New Industrials: An Investment Strategy for the Reindustrial Age (Part 1)

Part One: Framing

I. The Turn of History’s Wheel

From the climate crisis and pandemics to volatile geopolitics and systemic workforce displacement, the global system that we’ve known is being shaken to its core. It is disorienting, bleak, and at times, even shocking. But such systemic change is not new.

Throughout the course of human history, periods of mass disruption tend to signal the end of one epoch and the beginning of another: the future unfolding itself before us. More recently, our understanding of these cycles is often viewed exclusively through the lens of financial markets. However, with a long enough time series to frame one’s perspective, a more holistic mosaic appears. Cycles are driven by major technological advancement, both disruptive and non-obvious in its time.

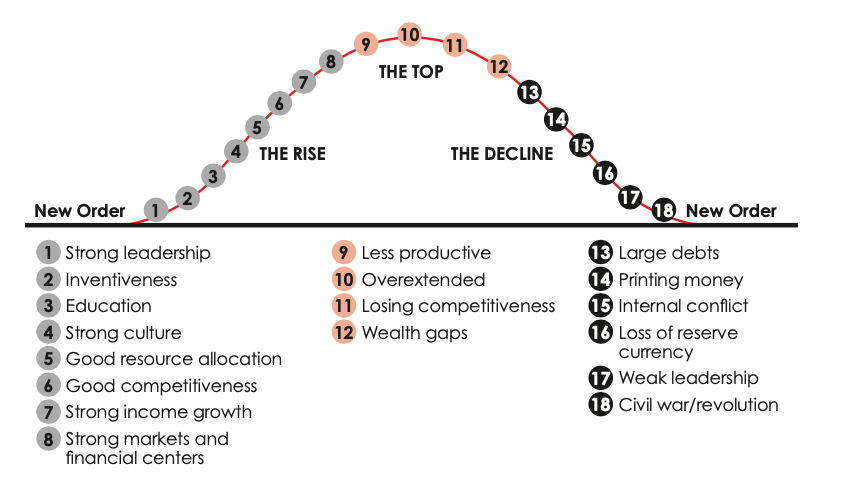

There have been varying analyses of this type of disruption in the last years from the likes of Robert Kaplan, Daniel Yergin, and Peter Frankopan, to name a few. In Ray Dalio’s recent ‘Principles’, he describes this period as the archetypical “Big Shift’’, a reordering of the world’s wealth and power that affects multiple markets simultaneously. In the course of that realignment, innovation and new technologies are some of the leading indicators that a New Age is upon us.

From “Principles: The Changing World Order”

Nowhere are symptoms of the Big Shift more evident than in private markets. In the last thirty years, investors have focused overwhelmingly on the proliferation of software. As Marc Andreessen now famously wrote, software has “eaten the world” and for good reason. Software-as-a-service has become easy to build, distribute, and monetize. Buoyed by a tailwind of extraordinary government largesse in response to the Global Financial Crisis, venture capitalists went ‘all in’ on this paradigm, backing founders that leveraged software’s ubiquity to solve even the slightest inefficiencies in sectors ranging from human resources to short form entertainment. The result has been some of the most profitable business models and companies in the history of capitalism.

While we do not forecast an abrupt end to this previous era, we do see its persistence as the dominant trend beginning to wane. As the great challenges of our time have increased in severity, so too has the urgency to address them. For solutions, entrepreneurs, investors, and policymakers alike have turned an eye to the fringes, where remarkable advancements in innovation and technology have been quietly gaining momentum.

II. The Internet spawns the Information Age

Throughout time, humanity has been granted temporal powers through the discovery of new technology. In many cases, its discovery and further innovation has been the spark to accelerate the transition from one cycle to another – consider the compass, the printing press, the internal combustion engine, the telephone, the light bulb, penicillin, and radar. Whole industries were then built around these technologies and their champions rose to power.

Venture Capital before the Internet – backing a diversity of technologies

Venture capital as an asset class and underwriting model expanded in parallel to fund these many innovations.

As foundational R&D matured from universities and government- sponsored investment (e.g., DARPA), the “Internet” emerged to unleash a thirty-year investment boom, in which the industries of consumer electronics, telecom, and media transformed from analog technology bases and associated distribution systems to new, often disruptive digital foundations. This initial wave of digital reinvention established a center of gravity for innovation in Silicon Valley and eventually other startup ecosystems emerged.

These ecosystems gave birth to many successful companies, establishing new role models, technology best practices, and a feedback loop of entrepreneurial and investment partnership and risk taking. This positive symbiosis established a new speed and tenor of business, often displacing traditional industry or government-led investment models. As consumers and enterprises adopted the new digital platforms for communicating, working, entertaining, and learning, they quickly influenced market demands and market requirements. The market interplay between these new digital offerings (as replacements/substitutes) for established analog technologies transformed the flow of economics and reshaped the market structures of affected industries.

Rapid change and information overload emerged as a systemic reality – both as risk to manage and opportunity to exploit. The resulting shift in culture, politics, and civil society has been a harbinger of transformation and disruption, both for better and for worse.

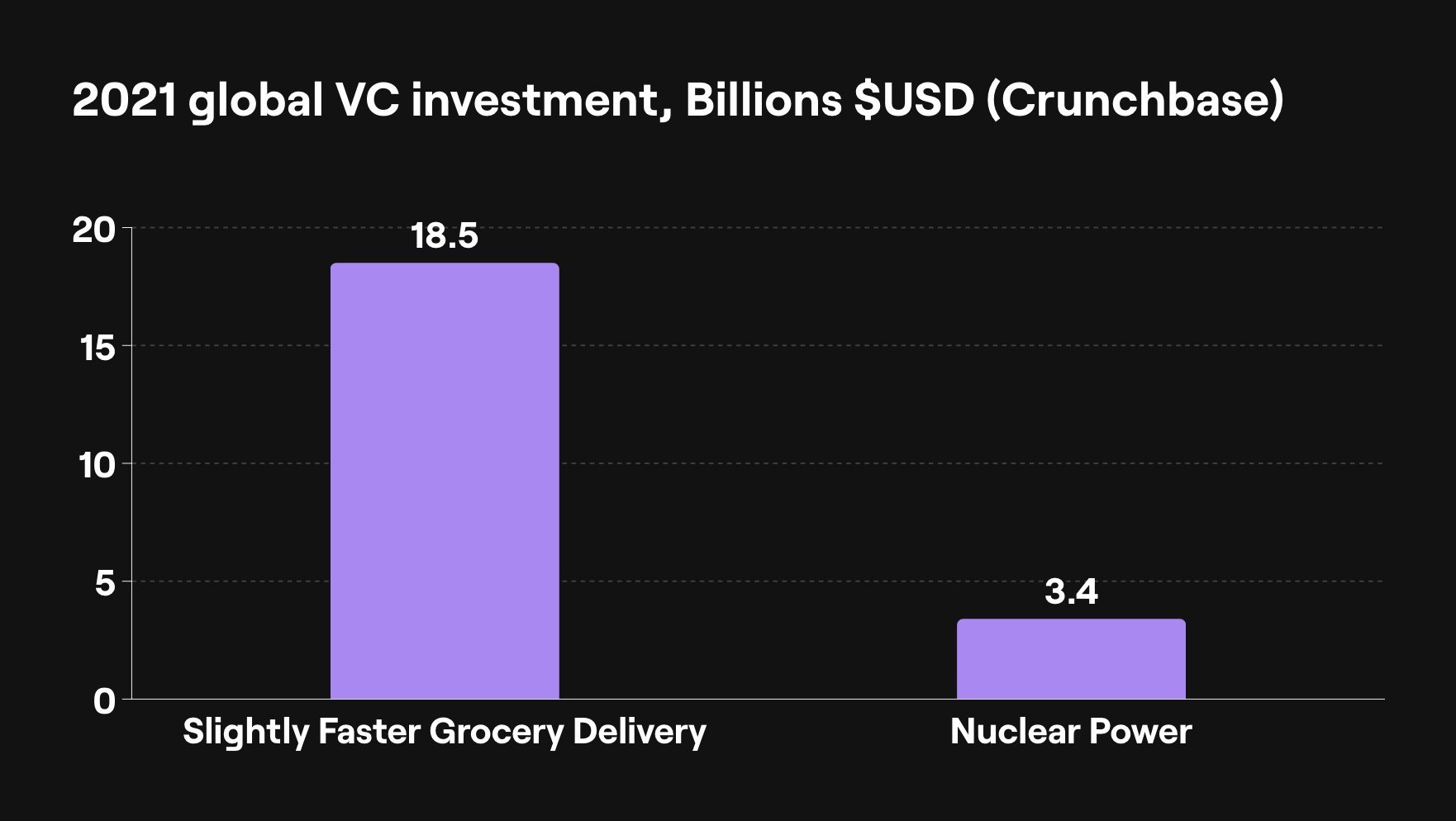

One important feature of these changes is that it narrowed the focus of innovation. Consider 2017. At this era´s near zenith, we marked all-time lows across democratic economies in foundational R&D funding but all-time highs in Internet-based funding (see the 2021 global VC investment graphic below for a further case in point). As investors looked to invest in the models and frameworks dominant in the early Information era, we witnessed billions of dollars chasing increasingly marginal utility for consumers and businesses. Software-based service economies (and broad financialization), displaced industrials as a focus, with the latter increasingly outsourced to a globalized economy where the division of economic value assumed an ever-increasing interdependence.

This was the assumed fruit of a globalized market economy where trade was the binding between a functionally integrated set of markets that developed in the calmer decades post the close of the Cold War. A market-centric China, an integrated Europe, a stabilized energy economy – these conditions set the context of the new millennium.

III. The Black Swan Reality

It is beyond the scope of this memo to fully unpack the many factors that shifted the mood from early optimism to one of growing anxiety. The events of 9/11, the War(s) on Terror in reaction, and the numerous simmering and hot conflicts with non-state actors utterly reshaped policies and national responses to global security. The challenge and debates on climate change rose to the status of “global crisis”, with all the associated politics and policy debate given its extra-national character. The 2008 global financial crisis highlighted and amplified the issues of wealth and social inequality. These events, and many other localized issues, quickened mainstream politics as an additional test of most governmental and institutional responses. One result has been an increasingly polarized set of political and market reactions to the numerous failures (real and perceived) of governmental and institutional response to these crises. Mismanagement and scandal have further eroded social trust to a level not seen since the 20th century.

This simmering brew of crisis and social disruption has erupted into a demand and urgency for effective action. The global pandemic and a return of industrial warfare in Europe in the last few years have launched a full-blown reassessment of the core assumptions underlying the globalized economy and highlighted the management deficiencies of most national and localized capacities. In the face of these unpredictable and large-scale impact events, organizations the world over are now required to reevaluate the fragility of interconnected systems and the need for resilience and rebuilding as an existential requirement. Black Swans are no longer “rare” but “expected”.

IV. Beyond the Information Age to the Reindustrial Age

This is the context under which technology-driven reindustrialization must deliver clear benefits and returns measured not only in financial terms but also in explicit forms of social capital. Take for instance power generation: the value of clean air and water as social goods will need to be priced going forward. Legacy infrastructures such as the electrical grids – designed decades ago with a simpler set of design objectives, will need to modernize against a broader set of requirements, sustainability lead among them. The increasing intensity of weather patterns is impacting many resource-based economies. In parallel, as the contest for development occurs in a resource constrained world, conflict and competition are changing in nature: militaries are adjusting not only to address the many non-state actor threats but with the return of great power rivalry, technology has become the essential “battlefront”. To address these challenges effectively, technology must extend from its Information Age parameters and into the industrial economy where software as an independent solution is not sufficient.

The industrial economy, while efficient and reliable, is not often characterized as particularly innovative. This is largely driven by the significant capital expenditure required to produce goods at scale while under constant market pressure to deliver threshold quality with attractive unit economics. It can be characterized as more rigid than flexible, incremental, and having a high threshold for change and innovation. And rightly so: it has provided a high quality of life and prosperity that modern market economies have come to accept and enjoy.

However, the era of persistent transformation we see unfolding is one in which the existing economic order is forced to utilize technology to reindustrialize and reinvigorate the legacy assets of the industrial economy that are essential to the operation of a functioning society. The old practices of globally outsourced manufacturing and localized service economies will not hold and need to be smartly rebalanced into hybrid models that are responsive and adaptable to the rapid emergence of this new and unsettling reality.

These new models are already entering the mainstream. It is the case that, as “software eats the world”, the tooling of the Information Age has advanced in applicable scope and now holds the potential to reinvent every aspect of the modern industrial economy. We are witnessing the emergence of new technology and its infrastructure complement that continues to unlock the “datasets” of the world (from the light switch and power meter to the vast genomes of the planet’s life). These advances are enabling the creation of new energy sources, programmable biology, and the advent of decarbonization technologies that are needed to address the generational problem sets we collectively face.

V. The Emergence of New Industrials

This new era is well-underway. Innovation across the diversity of the technology stack is driving a reorientation of industrial economies. We are witnessing the rapid emergence of a paradigm in which multiple global industries, such as those listed below, are all undergoing transformation simultaneously.

Energy: a shift to renewable energy (production, storage, distribution)

Mobility: transportation without fossil fuels

Food systems / Agriculture: fundamental shifts in feedstock, supply chains, and consumption

Circularity: the replacement of carbon and petrochemicals as the industrial backbone

Computation / AI + ML: Step changes in data processing and human meets machine innovation

Health: Standardized to personalized medicine and from symptomatic to proactive healthcare

Different from the previous era, the companies being formed are not confined to one technology vertical. To transform a legacy industry like agriculture, petrochemicals, or aviation, technology convergence must be a design tenet. Therefore, entrepreneurs are building solutions that are software-centric but integrate hardware, biology, data, laboratories, factories, and even farmland.

We call the companies that pioneer these solutions – New Industrials – and we believe that the most valuable company of the 2030s (by global market cap) will be a New Industrial.

VI. A New Class of Builders

Not surprisingly, New Industrials are being created by an expansive new class of entrepreneurs. They are mechanical engineers, molecular biologists, physicists, rocket scientists, experienced investors and operators, military and intelligence veterans, policy wonks, and designers. Like the Traitorous Eight of Fairchild Semiconductor or the Homebrew Computer Club, these entrepreneurs embody the era that they are living in and are motivated by the power of technology to solve extraordinary problems.

They are natives of this transformation and are themselves products of it. They are mission-driven, embracing the ethos that the problems we face today cannot be solved solely with the approaches of the previous cycle. However, they are also students, operating with a deep appreciation for the vast store of human capital and hard-won lessons of prior generations of builders. They are values-based but not ideological purists. They are multi-disciplinary in outlook, building approaches that integrate and synthesize varied skill sets and observed best practices. They are pragmatists, recognizing that this transition will not succeed if only defined by philanthropic goals or corporate ESG promises, but rather require a fundamental reordering of wealth and power through technological development. The best of them understands that the rich asset base they inherit from legacy industries can be smartly reimagined without onboarding crippling legacy constraints.

For them, above all, the mission reigns supreme. It is the definitive thread that runs through how their teams are built, resources are allocated, and performances are measured.

VII. The Mission-Aligned Investor

However, these builders and entrepreneurs are increasingly met with a harsh reality – an efficient financing model to match their mission does not yet exist. In the Information Age, private market investors, particularly venture capitalists, evolved to meet the needs of software-centric businesses. To determine a company’s progress and ultimately investment attractiveness, investors and entrepreneurs developed a set of shared formulaic processes and universal terminology such as DAU, MAU, and CAC. The result was the commoditization of financial products to service each step in their development, from company formation to public offering.

New Industrials are a much different animal. There are not yet proven templates and / or minimum viable products for investors to replicate. As in the early days of the Information Age, the technology and the industry around these companies are being built and evolving simultaneously.

Capex ($ trillions) requirement by industry, McKinsey, 2022

As illustrated above by McKinsey, the capital requirement needed to fully transform these industries is staggering. And while much of it will be fulfilled in the coming decades by later-stage institutional investors, governments, and sovereign wealth funds, there is still significant work and risk for any company, regardless of the quality of their innovation, to reach that universe of capital.

At this stage therefore, there is far less distinction between the investor and the entrepreneur. Innovation is just as necessary in the approaches and models to investing in New Industrials as it is to invent them. A New Industrial investor must understand and draw actionable linkages between the innovation and the very industry it is seeking to disrupt, operating at the intersection of decreasing technological risk and increasing commerciality.

Just as J.P. Morgan founded an institution to create financial frameworks for the emergent industries of the American Industrial Revolution and Marc Andreessen followed in software, the investor entrepreneurs that build a center of gravity for these founders and their technologies will create this generation’s defining institution.

VII. Acequia Capital’s Lessons applied to the New Industrials

The team we have built is uniquely positioned to provide leadership and the best-in-class platform for mission-driven companies and mission-aligned investors. For twenty-five years, Hank Vigil helped build Microsoft into one of the most successful global technology companies. Microsoft provided an apex vantage point to operate and learn as software grew beyond the PC and corporate network, to the edge device and the “cloud” compute platform. As Microsoft’s Head of Strategy and Partnerships, Hank helped Microsoft navigate through multiple platform transitions and the challenges of operating coherently across Microsoft’s 17 separate billion-dollar profit centers. Hank operated by forming and leading virtual teams of Microsoft’s best talent drawn from the relevant divisions when leading strategic corporate level initiatives (the Yahoo acquisition, the Facebook investment, the Nokia partnership, and several private antitrust settlements, to name a few). This experience applies directly to identifying and advising founders and teams now working at the emerging edge of technology and market change.

Hank participated in a number of highly contested and competitively intense battles that raged inside the technology industry itself as it matured: the browser wars as Netscape helped the internet go mainstream; Apple’s return from the dead to become the technology leader for personal devices and mobility that displaced the desktop; the Search Wars as Google established dominance; and Facebook (where Hank led the Microsoft investment into the company), which established a new dimension to the browser and email centric web experience, as the “Social graph” emerged to establish digital identity and targeted advertising.

Literally next door, Amazon evolved from an online book seller to become the transformative leader of online commerce. Amazon’s subsequent success in building its hyperscale “cloud compute” platform and the associated physical supply chain and logistics assets influenced Acequia’s thinking on how technology disrupts and shifts traditional incumbent market power. Amazon – as it increasingly shifts commerce from the brick-and-mortar world to the “Web”, is a concrete example that informs the Acequia Capital approach to New Industrials. We see many like cases where a traditionalist “industry” is giving way to new technology approaches. Industry leaders are learning the core technology tenet: reinvent or perish.

Through general partner Leif Danielsen’s approach, Acequia Capital has established a deep trust with founders via proven advice and countless hours helping founders successfully navigate all the early bumps of the startup journey. Leif has proven that Acequia is “founder centric” as a first principle, often as the one voice highlighting issues and risks that other venture investors avoid or miss. Collectively the team has applied the lessons of community ecosystems to the concept of the “founder network”, which has been a constant focus of our effort. The Acequia founder network is now a resource for every new addition, whether a builder or a peer investor/partner. It is geographically distributed, reflects the diversified technology skillset of the founder base, and operates as a trust-based franchise that is a core enabling asset.

Over the last decade, Acequia Capital’s early-stage approach led to investments and partnerships with many founders building at the emerging edge of the New Industrials. This portfolio, which includes over 400 companies, is a wellspring for many next stage New Industrial investments. Examples include Radiant Nuclear, Atomic Industries, Prewitt Ridge, FormLabs, and Tulip Manufacturing.

The Acequia Capital team recognizes the dynamics outlined throughout this memo - a moment where early-stage new industrial companies, as they mature, will require innovative business approaches to scale and assume leadership in their respective industries. This will consist of new approaches to capital formation, including project financing, an ability to engage advisors that can help navigate shifting regulatory frameworks, and developing a model of accretive partnership with governmental and public sector actors.

Concurrently, a frequent Acequia co-investor and market ally – Gregory Bernstein – was reaching a similar set of conclusions at EQT Ventures. As an investor in many of EQT Ventures’ New Industrial portfolio, Gregory recognized that the current capital stack was ill-suited for companies he was responsible for – even at an institution with the size and scale of EQT. He believed that the investor and entrepreneur were evolving simultaneously in this space and that a new approach, what he called “In Service of Mission”, would be necessary to capture the opportunity. Once Greg and the Acequia team recognized their shared thesis, Greg agreed to join as a General Partner to lead this strategy and Acequia Capital New Industrials was born.